|

|

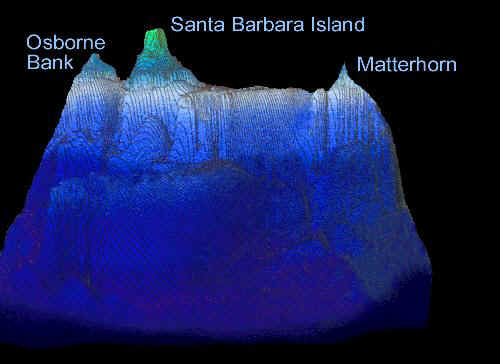

The Santa

Barbara Alps Copyright 1995-2009 by Eric Maiken

|

BathymetryLooking southwest across Southern California's Santa Monica basin, the Matterhorn pinnacle, Santa Barbara Island, and Osborne bank rise from a common buttress in the Santa Barbara Alps.

|

|

|

|

Click to View Scaled Plot (vertical 30x horizontal) |

Matterhorn | |

|

The three photos give you an idea of just how much stuff is clinging to the Matterhorn... "Life piled on life!" You can make out purple, red, orange, and pink Corynactis anemones --many the diameter of a silver dollar. Besides the clingy things on the rocks, there are all kinds of big fish, including Wolf Eels, Yellowtail, Mola Mola, Starry and Rosy rockfish. This large Mola Mola

hung around to watch deco. You can often locate the pinnacle by observing

birds, sea lions, and other animals congregating on the surface above the

mountain. Kathy Koprivnikar was, perhaps, the first woman to

dive Matterhorn in 1994. The cover story of the December, 1971 issue of Skin Diver Magazine was Jack McKenney's "A Dive on the Matterhorn."

A page from Jim Baden's 1990s log book." |

The following article was published in a substantially different form as "Matterhorn" in the "Image" section of aquaCORPS N.10 Imaging the Deep (Summer 1995). The slopes of Southern California's western mountains rise from abyssal rather than coastal plains. Along submarine ridges, some peaks clear the sea's surface, forming the Channel Islands. Others lie below surrounding waters as seamounts. These blue water oases provide technical divers with some of the best reef diving off the West Coast of North America. Towering as much as a mile above the sea floor, a few sentinel peaks and ridges form pinnacles and banks that offer a reverse mountaineering challenge. Two submerged summits ride the same buttress as Santa Barbara Island. Osborne Bank is a long ridge with miles of terrain between 200 and 120 feet deep. The Matterhorn pinnacle is aptly named for its extremely sharp profile--only a few square yards lie shallower than 200 feet. First dived more than twenty years ago by an adventuresome few (including Cousteau), Matterhorn was even the subject of an article in the bold Skin Diver Magazine of the Seventies. In the ensuing years, the sharp pinnacle eluded casual divers who searched in vain for the feature mischarted as only 17 fathoms. With the peak actually lying nearly 130 feet deep, twenty nautical miles offshore, Matterhorn long remained far from the sport diving itinerary, with most of the boats plying the area loaded with fishermen rather than divers. Enticed by rumors of big diving, Jim Baden led the first group of technical divers to the site in 1992. Strong currents often flow over the uppermost ridges of the mountain as water blown by wind and drawn by tide funnels through nearby channels. The easiest diving is near sheltering walls and bowls, well below the ridge lying perpendicular to the one-to-two knot flow. Due to the difficult terrain, currents, and opposing surface winds, it is prudent to count on diving in the 200-foot range, at nearly twice the charted depth. Divers should personally carry all decompression gas because anchors have slipped off the mountain during hangs. While Osborne Bank's location behind Santa Barbara Island isolates it from the heavy flow of the near-shore channel, currents are still a factor there as well. The underwater mountains offer divers challenges and beauty that are unmatched by any of California's near-shore diving sites. Though currents hazard divers, they bring nutrients and animals to the banks. Taking advantage of the overdriven engine of life, the most spectacular concentrations of invertebrates found in Southern California cover the mountain walls. Creatures normally ranging far to the north and south are stranded on the lonely outposts, while some of the most common plants and animals of the nearby islands are absent. The severe yet fragile environments of the seamounts are hospitable only to those creatures with the ability to match a strong drive for survival. Those who go down to the mountain tops should strive to preserve these underwater islands --along with their own lives. |

Decompression | |

|

|

The profile

compares stops calculated by the Varying Permeability Model (VPM) to the

schedule calculated by aquaCorps' editors using a commercial

program. All times are run-times in minutes, depths are in feet. Note that

the VPM starts your stops much deeper than the published profile, and gets

you out of the water a bit later. The dive modeled, shown as the magenta

line, expressed as depth/run-time is: 200 ft/13 min -- 160 ft/26 min --

130 ft/37 min on air. The ascent is on air until 20 ft, where the switch

to oxygen is shown as a green line. Even thought the VPM plot shows a 10

ft stop, I'd pull it at 20 ft.

If you'd like a copy of the nitrox VPM program, see the bubble model decompression program page for details. |

|

| |

AcknowledgementsaquaCORPS article thanks to: Michael Menduno and Michael Bielinski. |